Jan

22

2019

Written by Noelia Mann

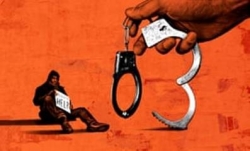

Illustration: Rob Dobi

It’s been about a month since Jazmine Headley’s son Damone was ripped from her arms in the Human Resources Administration building in Boerum Hill, where she had gone to try to get her child-care benefits reinstated. You may have seen the disturbing video of what happened, and you wouldn’t be alone- it’s been watched over 1.3 million times and has propelled Ms. Headly into the center of a public reckoning over how the city treats people seeking public assistance. But the conversation has already been going on for a long time among individuals seeking services in New York and elsewhere, who say Jazmine’s experience isn’t unique. Rather, it’s part of an American tradition of scorning those experiencing poverty and viewing access to public assistance as a privilege. The punitive and retaliatory compliance culture evident in Jazmine’s case reflects a national culture that punishes the poor and shames those in need of services. The dehumanizing effects of that culture aren’t lost on Jazmin. “They never asked me my name,” she shared in an interview with the New York Times. “They never said, ‘Hello, who are you?’”

At the Building Movement Project, we’ve spent over fifteen years supporting direct service organizations as they make shifts towards acknowledging the humanity, dignity, and power of the individuals seeking their services. Part of that shift is linguistic. Renee Ho wrote a wonderful article about this in which she explains;

In the act of naming, subjects are born. In the act of reiterating the name, power dynamics, inequalities, and structural violence are reinforced. And so it is with the word ‘beneficiary.’ To be a beneficiary implies a relational weakness to the benefactor. It also implies that what she receives is bene or good. Descriptively, beneficiary partially works: in the current system of aid and philanthropy beneficiaries are, in fact, largely disempowered; at the same time, however, it’s questionable that what they’re receiving is all that bene.

Bearing the power of language in mind, Ms. Ho offers a variety of alternatives, including citizen and stakeholder. At BMP, we use the term “constituent” to expand the view of participation to include individuals, family members, residents and members of other organizations that are connected to the organization. It also helps reinforce the connection between service delivery and organizing for political power because constituent can also mean a member of a “constituency”: a body of citizens entitled to elect a representative (as to a legislative or executive position).

In Jazmine’s case, however, it is all too clear that no matter what she had been called- client, beneficiary, even her name- the underlying power differential and the disdain with which she was viewed for being in that office wouldn’t have changed. The more important shift here is one of mindset, and subsequently, of action. Beyond rejecting racist narratives about the “undeserving” poor, we need to move away from a “beneficiary” mindset, in which individuals seeking services are viewed as people in need, and towards a “constituent mindset,” in which they are recognized as integral partners in the effort to build long-lasting solutions for communities. This deeper, more difficult shift requires organizations to examine power dynamics within their programs, and in their relationship to constituents and the community at large.

So, how can we push ourselves and our organizations away from a beneficiary mindset? We can start by asking “Hello, who are you?” and actually listening to the answer. In February, Kea Mathis from the Detroit Peoples’ Platform and Reverend Roslyn Bouier will join our Tools to Engage webinar series to talk about the steps they’re taking in Detroit to reaffirm the humanity, dignity, and power of individuals requiring assistance. Together, we’ll talk about the criminalization of asking for help, what it looks like when people are asked about what they need and the answers are actually considered, and how service providers and organizers can work together to advance the common good of a community. Stay tuned for more info to register for this free webinar.