Mar

18

2020

Written by Sean Thomas-Breitfeld

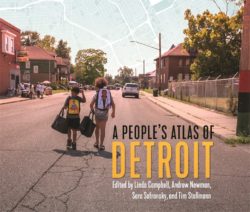

A new book titled A People’s Atlas of Detroit, co-edited by Linda Campbell, who directs BMP’s work in Detroit, narrates the lived experiences of people engaged in political battles central to Detroit’s future and that of urban America. The book features contributions by over fifty leaders from movement-building efforts in Detroit, including activists, farmers, students, educators, scholars, not-for-profit and city government workers, and members of neighborhood block clubs.

By drawing upon the maps, poetry, interviews, photographs, essays, and collective analyses of Detroiters engaged in the front lines of struggle, A People’s Atlas of Detroit argues that it is only by confronting racial injustice and capitalism head-on that communities can overcome the depths of economic and ecological crises afflicting cities today.

BMP’s Co-Director, Sean Thomas-Breitfeld, interviewed Linda Campbell to learn more about this innovative, community-based, participatory research project.

What is the People’s Atlas and how did this project come together?

The People’s Atlas includes contributions by way of stories, poetry, art, and artifacts from about 50 Detroit activists and advocates who have engaged in movement work here in the city, I’d say over the last two to three decades. The People’s Atlas grew out of the movement work here in Detroit that was spearheaded around the state takeover, which formally occurred in 2012 through the consent agreement, but really was rooted in decades long disinvestment.

A group of folks came together and started investigating what in fact was happening across our city as early as 2011 with a particular focus on land because we were starting to see the incredible land grabs that were following on the heels of the great recession and the subprime lending collapse. The foreclosure crisis hit Detroit particularly hard. And at one time we had the highest number of foreclosures, I think in history in America. And so a group of activists and residents across the city became alarmed at the rate that we were losing land, and control of land here in Detroit. The devaluation of our land, the selloff of our land, and began to think about how the city was being restructured through the lens of geography and land.

We began to look at this question of spatial injustice. We started doing our own mapping about these processes, the sell offs, the land speculation. We looked at which communities were being hit the hardest, where the gentrification was occurring. We started bringing residents together to make their own statements about land, what they wanted to see in their neighborhood, what community land control might look like. We went around the city holding workshops and trainings, and helping people figure out how to map their community, how to think about spatial justice in terms an equitable and racially just built environment.

So this all kind of bubbled up from the ground and as a part of it, we encouraged folks to tell their story about their relationship to Detroit, through writing a essay or poem, something like that. So that is both the genesis of this project and the conceptual framing for the People’s Atlas.

Part of what makes the People’s Atlas such a remarkable achievement is how long it has been in the works. How did you keep people organized, engaged and informed so that they would stick with this lengthy process over the past decade?

Well, I don’t know if I would characterize it as a “remarkable accomplishment” but as editors, we’ve taken responsibility for shepherding the process, maintaining relationships, being in touch with those who have contributed, and then writing the atlas took quite a bit of time as well.

The organizing work we were doing back in 2011, which would eventually lead us on a path towards producing the Atlas, has outlasted many changes in the city. What’s been difficult is organizing in the moment, and there have been a number of emerging crises to respond to here in the city. For example, there were water shut offs happening until the recent coronavirus outbreak amplified the pressure from activists. Also, gentrification has really ramped up in Detroit since we started working on the Atlas. We’ve also lost some of the activists who had been involved in this project early on. My dear friend Lila Cabbil – a founder of the People’s Water Board Coalition and Detroit People’s Platform – made her transition last year, so she didn’t live to see the People’s Atlas published. Also, Charity Hicks – who was also a founder of the People’s Water Board Coalition – has been gone almost six years. Those are women who are no longer with us, but when you open up the People’s Atlas, you’ll see their words right there.

Now we’re at the point in the process where we are trying to gather everyone together to celebrate the publication and to do some reflecting on this the path that we traveled. What does our future look like together? How does A People’s Atlas of Detroit serve as the launch for new movement work in the city? And how can the atlas be a really useful tool for the next generation of movement makers here?

Even though the People’s Atlas is published by a university, it’s not a traditional work of research. What was the process of partnering with academics to produce this book?

The partnerships that were developed between the academics who were involved in pulling this project together and the actual creation of the People’s Atlas, that partnership sort of pre-dated the idea of the atlas. So really we didn’t come together around the idea of, “Oh let’s produce an Atlas.” I happened to meet both Sara Safransky and Andy Newman through work in the community. Sara was a PhD student and she was studying here in Detroit to figure out what was going on around the dispossession of land and the land grabbing that was going on in the city. I met Andy Newman at a community event and we developed a relationship where he would have students come and work with us as interns doing some really important participatory research. Tim was someone that Sara and Andy had known, he was interested in mapping and cartography and so he brought that skill to the table. So that’s the editing team.

I’d worked with academics before and had sort of a bad taste in my mouth. My work with academics goes all the way back to the HIV/AIDS crisis where I saw how academics often came into the community and extracted all kinds of information from folks. Back then it wasn’t called participatory research, but it was a way of collecting data and information that really enriched their knowledge and their standing and sort of grounded a lot of these professors in becoming experts on HIV in communities of color. Most of those community members were left with nothing. They didn’t receive a fair share of acknowledgement in terms of helping to co-create that knowledge. They certainly didn’t receive any kind of monetary reimbursement for it. And so as a result of that, I was very reluctant to work with academics.

One of the things that I really liked about Andy and Sara is that they brought resources to the table. They avoided that usual power dynamic and relationship that you see with a lot of academics where they’re the gatekeepers to the knowledge and resources, they have these powerful institutions that sort of sanction who they are and legitimize their work, and they end up extracting a lot of knowledge and energy from community and give very little back. Sara and Andy sort of reversed that normal process and came to the table helping to write grants, always making sure that monies were available to community, whether it supported an intern or supported additional research, or just to help give nonprofits funding to sponsor community events. They were always really mindful of whose knowledge and ideas were being lifted up. They would never publish information without vetting it with me and others on the ground. So it was just a different approach.

What working with them helped me do is formalize a protocol for how to work with academics. Recently, I ended up sharing with one of our community groups here in the city who had been totally exploited by an academic who ended up capturing a lot of information from community members. never shared that it was going to be part of a formalized paper and didn’t give community the kind of credit they deserve for the knowledge and expertise that they hold about gentrification in Detroit. When community members came to me outraged about that situation, I was able to lay out things to think about in the future about how academics should show up in community, what kind of relationship to expect, and what the power arrangement between researcher and community should look like.

Ok, last question. For people working in the nonprofit sector across the country, what would you want them to learn or come to appreciate by reading A People’s Atlas of Detroit?

Well, I think one of the things to be appreciated is the dynamic history of Detroit, particularly through the lens of Detroit as a majority black city. Detroit is a place where progressive movements and a commitment to equity and justice, particularly for Black and working-class folks, have been alive and thriving for all these years. But that story often has sort of disappeared recently. So I think the People’s Atlas documents that movement energy in a really good way. It’s a cross-generational portrayal of Detroit that I think you don’t see too often in the city. And I think it’s a celebration of Detroit, the resilience, the vision, just the incredible talent of Detroiters and their desire to make Detroit the incredible place that it, it deserves to be as the nation’s largest majority-Black city.